The Continuation War, also known as the Second Soviet-Finnish War, was a conflict fought by

Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of B ...

and

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

against the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

from 1941 to 1944, as part of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

.; sv, fortsättningskriget; german: Fortsetzungskrieg. According to Finnish historian Olli Vehviläinen, the term 'Continuation War' was created at the start of the conflict by the Finnish government, to justify the invasion to the population as a continuation of the defensive

Winter War

The Winter War,, sv, Vinterkriget, rus, Зи́мняя война́, r=Zimnyaya voyna. The names Soviet–Finnish War 1939–1940 (russian: link=no, Сове́тско-финская война́ 1939–1940) and Soviet–Finland War 1 ...

and separate from the German war effort. He titled the chapter addressing the issue in his book as "Finland's War of Retaliation". Vehviläinen asserted that the reality of that claim changed when the Finnish forces crossed the 1939 frontier and started annexation operations. The US Library of Congress catalogue also lists the variants War of Retribution and War of Continuation (see authority control)., group="Note" In Soviet historiography, the war was called the Finnish Front of the Great Patriotic War.. Alternatively the Soviet–Finnish War 1941–1944 (russian: Советско–финская война 1941–1944, links=no).

, group="Note" Germany regarded its operations in the region as part of its overall war efforts on the

Eastern Front and provided Finland with critical material support and military assistance, including economic aid.

The Continuation War began 15 months after the end of the

Winter War

The Winter War,, sv, Vinterkriget, rus, Зи́мняя война́, r=Zimnyaya voyna. The names Soviet–Finnish War 1939–1940 (russian: link=no, Сове́тско-финская война́ 1939–1940) and Soviet–Finland War 1 ...

, also fought between Finland and the USSR. Numerous reasons have been proposed for the Finnish decision to invade, with regaining territory lost during the Winter War being regarded as the most common. Other justifications for the conflict included Finnish President

Risto Ryti

Risto Heikki Ryti (; 3 February 1889 – 25 October 1956) served as the fifth president of Finland from 1940 to 1944. Ryti started his career as a politician in the field of economics and as a political background figure during the interwar perio ...

's vision of a

Greater Finland

Greater Finland ( fi, Suur-Suomi; et, Suur-Soome; sv, Storfinland), an irredentist and nationalist idea, emphasized territorial expansion of Finland. The most common concept of Greater Finland saw the country as defined by natural borders enc ...

and Commander-in-Chief

Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim's desire to annex

East Karelia. Plans for the attack were developed jointly between the ''

Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the '' Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previo ...

'' and a faction of Finnish political and military leaders, with the rest of the government remaining ignorant. Despite the co-operation in the conflict, Finland never formally signed the

Tripartite Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also known as the Berlin Pact, was an agreement between Germany, Italy, and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940 by, respectively, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Galeazzo Ciano and Saburō Kurusu. It was a defensive milit ...

, though it did sign the

Anti-Comintern Pact

The Anti-Comintern Pact, officially the Agreement against the Communist International was an anti-Communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on 25 November 1936 and was directed against the Communist International (C ...

. Finnish leadership justified its alliance with Germany as self-defence.

On 22 June 1941,

Germany launched an invasion of the Soviet Union. Three days later, the Soviet Union conducted an air raid on Finnish cities, prompting Finland to declare war and allow German troops stationed in Finland to begin offensive warfare. By September 1941, Finland had regained its post–Winter War concessions to the Soviet Union: the

Karelian Isthmus

The Karelian Isthmus (russian: Карельский перешеек, Karelsky peresheyek; fi, Karjalankannas; sv, Karelska näset) is the approximately stretch of land, situated between the Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga in northwestern ...

and

Ladoga Karelia

Ladoga Karelia ( fi, Laatokan Karjala, russian: Ладожская Карелия, Ladožskaja Karelija, Карельское Приладожье, ''Karelskoje Priladožje'' or Северное Приладожье, ''Severnoje Priladožje'') is a ...

. However, the Finnish Army continued the offensive past the 1939 border during the

conquest of East Karelia, including

Petrozavodsk

Petrozavodsk (russian: Петрозаводск, p=pʲɪtrəzɐˈvotsk; Karelian, Vepsian and fi, Petroskoi) is the capital city of the Republic of Karelia, Russia, which stretches along the western shore of Lake Onega for some . The population ...

, and halted only around from the centre of

Leningrad

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

. It participated in

besieging the city by cutting the northern supply routes and by digging in until 1944.

In

Lapland,

joint German-Finnish forces failed to capture

Murmansk

Murmansk (Russian: ''Мурманск'' lit. "Norwegian coast"; Finnish: ''Murmansk'', sometimes ''Muurmanski'', previously ''Muurmanni''; Norwegian: ''Norskekysten;'' Northern Sámi: ''Murmánska;'' Kildin Sámi: ''Мурман ланнҍ'') ...

or to cut the Kirov (Murmansk) Railway, a transit route for Soviet

lend-lease equipment. The conflict stabilised with only minor skirmishes until the tide of the war turned against the Germans and the Soviet strategic

Vyborg–Petrozavodsk Offensive occurred in June 1944. The attack drove the Finns from most of the territories that they had gained during the war, but the Finnish Army halted the offensive in August 1944.

Hostilities between Finland and the USSR ended with a ceasefire, which was called on 5 September 1944, formalised by the signing of the

Moscow Armistice

The Moscow Armistice was signed between Finland on one side and the Soviet Union and United Kingdom on the other side on 19 September 1944, ending the Continuation War. The Armistice restored the Moscow Peace Treaty of 1940, with a number of mo ...

on 19 September 1944. One of the conditions of this agreement was the expulsion, or disarming, of any German troops in Finnish territory, leading to the

Lapland War

During World War II, the Lapland War ( fi , Lapin sota; sv, Lapplandskriget; german: Lapplandkrieg) saw fighting between Finland and Nazi Germany – effectively from September to November 1944 – in Finland's northernmost region, Lapland. ...

between Finland and Germany.

World War II was concluded formally for Finland and the minor Axis powers with the signing of the

Paris Peace Treaties

The Paris Peace Treaties (french: Traités de Paris) were signed on 10 February 1947 following the end of World War II in 1945.

The Paris Peace Conference lasted from 29 July until 15 October 1946. The victorious wartime Allied powers (princi ...

in 1947. This confirmed the territorial provisions of the 1944 armistice: the restoration of borders per the 1940

Moscow Peace Treaty

The Moscow Peace Treaty was signed by Finland and the Soviet Union on 12 March 1940, and the ratifications were exchanged on 21 March. It marked the end of the 105-day Winter War, upon which Finland ceded border areas to the Soviet Union. The ...

, the ceding of the municipality of

Petsamo Petsamo may refer to:

* Petsamo Province, a province of Finland from 1921 to 1922

* Petsamo, Tampere, a district in Tampere, Finland

* Pechengsky District, Russia, formerly known as Petsamo

* Pechenga (urban-type settlement), Murmansk Oblast, Russi ...

(, ''Pechengsky raion'') and the leasing of

Porkkala Peninsula

Porkkalanniemi ( sv, Porkala udd) is a peninsula in the Gulf of Finland, located at Kirkkonummi (Kyrkslätt) in Southern Finland.

The peninsula had great strategic value, as coastal artillery based there would be able to shoot more than half ...

to the Soviets. Furthermore, Finland was required to pay US$300 million (equivalent to US$5.8 billion in 2021) in

war reparations to the Soviet Union, accept partial responsibility for the war and to acknowledge that it had been a German ally.

Because of Soviet pressure, Finland was also forced to refuse

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

aid.

Casualties were 63,200 Finns and 23,200 Germans dead or missing during the war and 158,000 Finns and 60,400 Germans wounded. Estimates of dead or missing Soviets range from 250,000 to 305,000, and 575,000 have been estimated to have been wounded or fallen sick.

Background

Winter War

On 23 August 1939, the Soviet Union and Germany signed the

Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that enabled those powers to partition Poland between them. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ri ...

in which both parties agreed to divide the independent countries of Finland,

Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, a ...

,

Latvia,

Lithuania,

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, and

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

into

spheres of interest

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal al ...

, with Finland falling within the Soviet sphere. One week later, Germany

invaded Poland, leading to the United Kingdom and

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

declaring war on Germany. The Soviet Union

invaded eastern Poland on 17 September. Moscow turned its attention to the

Baltic states, demanding that they allow Soviet military bases to be established and troops stationed on their soil. The Baltic governments

acquiesced to these demands and signed agreements in September and October.

In October 1939, the Soviet Union attempted to negotiate with Finland to cede Finnish territory on the

Karelian Isthmus

The Karelian Isthmus (russian: Карельский перешеек, Karelsky peresheyek; fi, Karjalankannas; sv, Karelska näset) is the approximately stretch of land, situated between the Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga in northwestern ...

and the islands of the

Gulf of Finland, and to establish a Soviet military base near the Finnish capital of

Helsinki

Helsinki ( or ; ; sv, Helsingfors, ) is the capital, primate, and most populous city of Finland. Located on the shore of the Gulf of Finland, it is the seat of the region of Uusimaa in southern Finland, and has a population of . The city ...

. The Finnish government refused, and the

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army ( Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, afte ...

invaded Finland on 30 November 1939. The USSR was expelled from the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

and was condemned by the international community for the illegal attack.

Foreign support for Finland was promised, but very little actual help materialised, except from Sweden. The

Moscow Peace Treaty

The Moscow Peace Treaty was signed by Finland and the Soviet Union on 12 March 1940, and the ratifications were exchanged on 21 March. It marked the end of the 105-day Winter War, upon which Finland ceded border areas to the Soviet Union. The ...

concluded the 105-day Winter War on 13 March 1940 and started the

Interim Peace

The Interim Peace ( fi, Välirauha, sv, Mellanfreden) was a short period in the history of Finland during the Second World War. The term is used for the time between the Winter War and the Continuation War, lasting a little over 15 months, from 1 ...

. By the terms of the treaty, Finland ceded 9% of its national territory and 13% of its economic capacity to the Soviet Union. Some 420,000 evacuees were resettled from the ceded territories. Finland avoided total conquest of the country by the Soviet Union and retained its sovereignty.

Prior to the war, Finnish foreign policy had been based on

multilateral guarantees of support from the League of Nations and

Nordic countries, but this policy was considered a failure. After the war, Finnish public opinion favored the reconquest of

Finnish Karelia

Karelia ( fi, Karjala) is a historical province of Finland which Finland partly ceded to the Soviet Union after the Winter War of 1939–40. The Finnish Karelians include the present-day inhabitants of North and South Karelia and the still-sur ...

. The government declared national defence to be its first priority, and military expenditure rose to nearly half of public spending. Finland purchased and received donations of war materiel during and immediately after the Winter War. Likewise, Finnish leadership wanted to preserve the

spirit of unanimity that was felt throughout the country during the Winter War. The divisive

White Guard tradition of the

Finnish Civil War

The Finnish Civil War; . Other designations: Brethren War, Citizen War, Class War, Freedom War, Red Rebellion and Revolution, . According to 1,005 interviews done by the newspaper ''Aamulehti'', the most popular names were as follows: Civil W ...

's 16 May victory-day celebration was therefore discontinued.

The Soviet Union had received the

Hanko Naval Base

Hanko Naval Base was a Soviet naval base from 1940 to 1941 in the town of Hanko at the Hankoniemi peninsula which is located 100 kilometers (62 mi) from Helsinki, the Finnish capital.

History

The Soviet Union had demanded from Finland ...

, on Finland's southern coast near the capital Helsinki, where it deployed over 30,000 Soviet military personnel. Relations between Finland and the Soviet Union remained strained after the signing of the one-sided peace treaty, and there were disputes regarding the implementation of the treaty. Finland sought security against further territorial depredations by the USSR and proposed

mutual defence agreements with

Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the ...

and

Sweden, but these initiatives were quashed by Moscow.

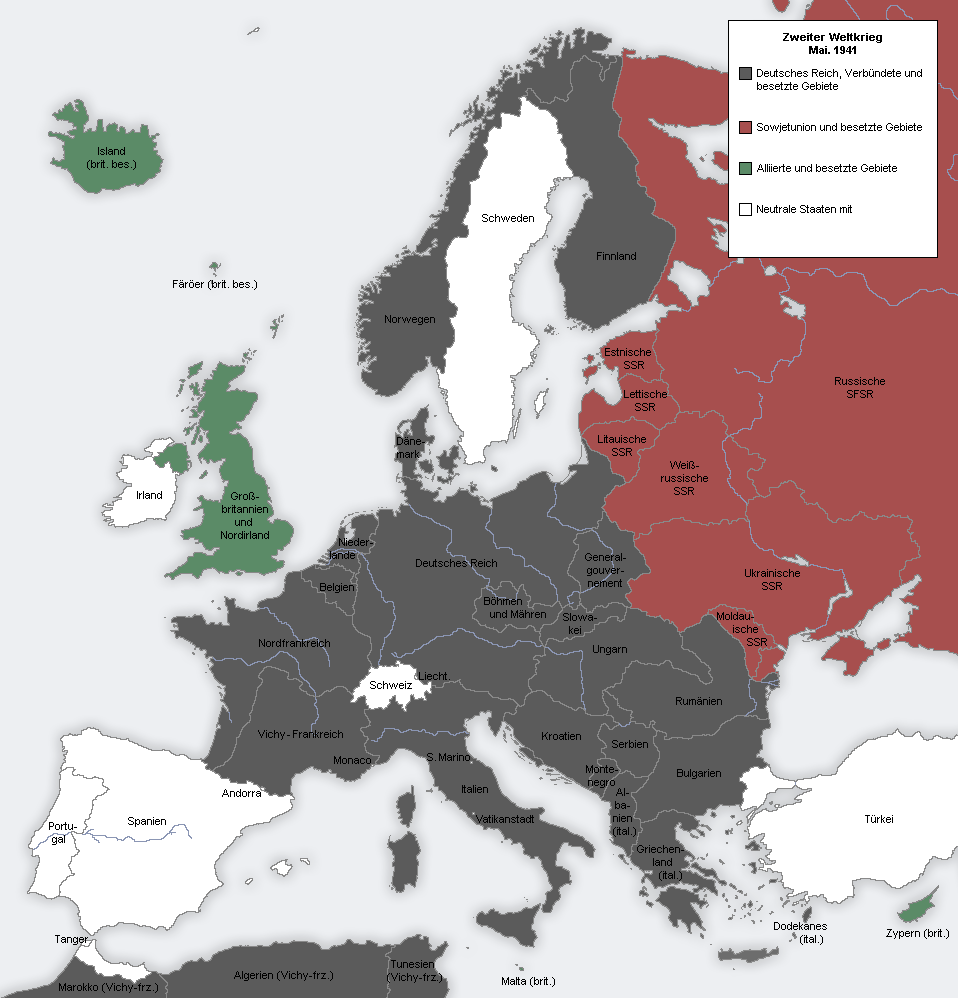

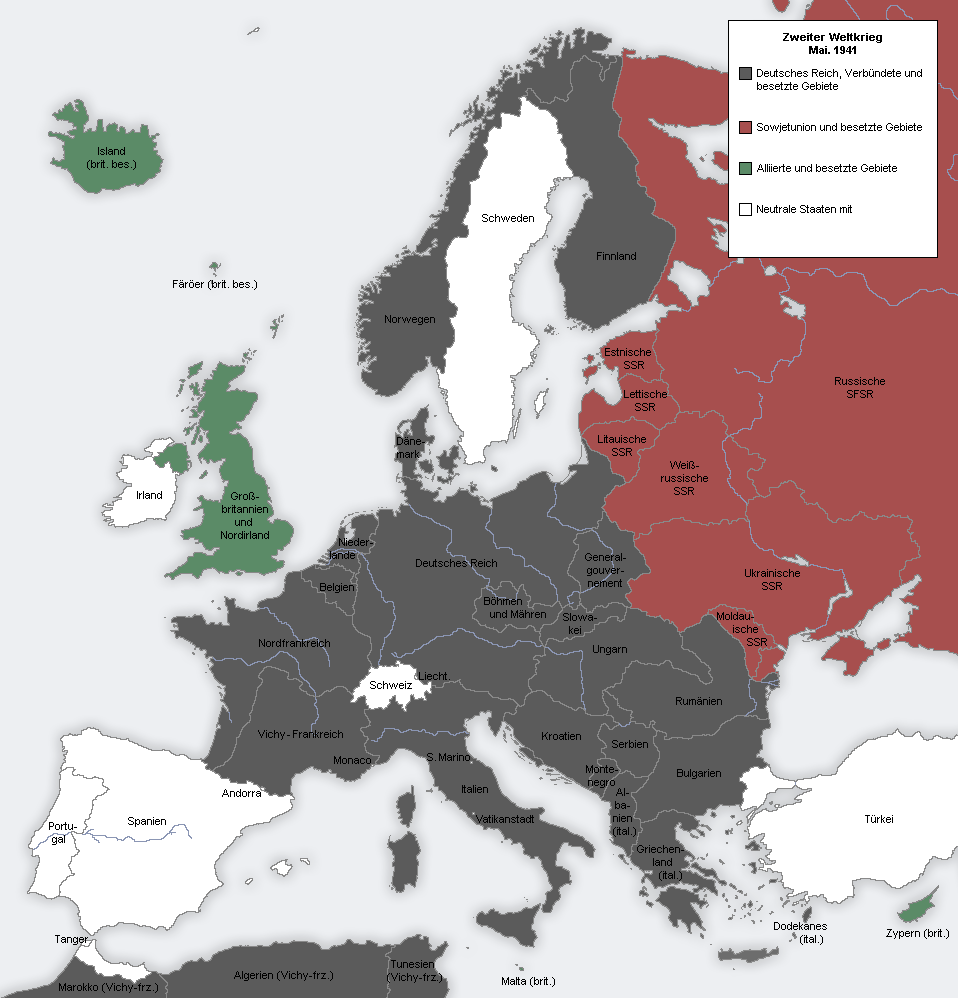

German and Soviet expansion in Europe

After the Winter War, Germany was viewed with distrust by the Finnish, as it was considered an ally of the Soviet Union. Nonetheless, the

Finnish government

sv, Finlands statsråd

, border =

, image = File:Finnish Government logo.png

, image_size = 250

, caption =

, date =

, state = Republic of Finland

, polity =

, cou ...

sought to restore diplomatic relations with Germany, but also continued its Western-orientated policy and negotiated a war trade agreement with the United Kingdom. The agreement was renounced after the

German invasion of Denmark and Norway on 9 April 1940 resulted in the UK cutting all trade and traffic communications with the Nordic countries. With the

fall of France, a Western orientation was no longer considered a viable option in Finnish foreign policy. On 15 and 16 June, the Soviet Union

occupied three Baltic countries almost without any resistance and Soviet

puppet regimes were installed. Within two months Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were incorporated into the USSR and by mid–1940, the two remaining northern democracies, Finland and Sweden, were encircled by the hostile states of Germany and the Soviet Union.

On 23 June, shortly after the Soviet occupation of the Baltic states began, Soviet Foreign Minister

Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

contacted the Finnish government to demand that a mining licence be issued to the Soviet Union for the nickel mines in

Pechengsky District

Pechengsky District (russian: Пе́ченгский райо́н; fi, Petsamo; no, Peisen; se, Beahcán; sms, Peäccam) is an administrative district (raion), one of the six in Murmansk Oblast, Russia.Law #96-01-ZMO As a municipal division, ...

(russian: Pechengsky raion) or, alternatively, permission for the establishment of a joint Soviet-Finnish company to operate there. A licence to mine the deposit had already been granted to a British-Canadian company and so the demand was rejected by Finland. The following month, the Soviets demanded that Finland destroy the fortifications on the

Åland

Åland ( fi, Ahvenanmaa: ; ; ) is an autonomous and demilitarised region of Finland since 1920 by a decision of the League of Nations. It is the smallest region of Finland by area and population, with a size of 1,580 km2, and a populat ...

Islands and to grant the Soviets the right to use Finnish railways to transport Soviet troops to the newly acquired Soviet base at Hanko. The Finns very reluctantly agreed to those demands. On 24 July, Molotov accused the Finnish government of persecuting the communist

Finland – Soviet Union Peace and Friendship Society and soon afterward publicly declared support for the group. The society organised demonstrations in Finland, some of which turned into riots.

Russian-language sources, such as the book ''

Stalin's Missed Chance'', maintain that Soviet policies leading up to the Continuation War were best explained as defensive measures by offensive means. The Soviet division of occupied Poland with Germany, the Soviet

annexation of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia and the Soviet invasion of Finland during the Winter War are described as elements in the Soviet construction of a security zone or buffer region from the perceived threat from the

capitalist

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, priva ...

powers of Western Europe. Postwar Russian-language sources consider establishment of Soviet

satellite state

A satellite state or dependent state is a country that is formally independent in the world, but under heavy political, economic, and military influence or control from another country. The term was coined by analogy to planetary objects orbitin ...

s in the

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist repub ...

countries and the

Finno-Soviet Treaty of 1948

left, 380px, Signing of the Finno-Soviet Treaty between the Soviet Union and Finland in Moscow on April 6, 1948. Signed by Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov, followed by Soviet Prime Minister Joseph Stalin. To the left of Stalin are ...

as the culmination of the Soviet defence plan. Western historians, such as

Norman Davies and

John Lukacs

John Adalbert Lukacs (; Hungarian: ''Lukács János Albert''; 31 January 1924 – 6 May 2019) was a Hungarian-born American historian and author of more than thirty books. Lukacs was Roman Catholic. Lukacs described himself as a reactionary.

L ...

, dispute this view and describe pre-war Soviet policy as an attempt to stay out of the war and regain land lost after the fall of the

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

.

Relations between Finland, Germany and Soviet Union

On 31 July 1940, German Chancellor

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

gave the order to plan an assault on the Soviet Union, meaning Germany had to reassess its position regarding both Finland and

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

. Until then, Germany had rejected Finnish appeals to purchase arms, but with the prospect of an invasion of Russia, that policy was reversed, and in August, the secret sale of weapons to Finland was permitted. Military authorities signed an agreement on 12 September, and an official exchange of diplomatic notes was sent on 22 September. Meanwhile, German troops were

allowed to transit through Sweden and Finland. That change in policy meant Germany had effectively redrawn the border of the German and Soviet spheres of influence in violation of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.

In response to that new situation, Molotov visited Berlin on 12–13 November 1940. He requested for Germany to withdraw its troops from Finland and to stop enabling Finnish anti-Soviet sentiments. He also reminded the Germans of the 1939 pact. Hitler inquired how the Soviets planned to settle the "Finnish question" to which Molotov responded that it would mirror the events in

Bessarabia and the Baltic states. Hitler rejected that course of action. In December, the Soviet Union, Germany and the United Kingdom all voiced opinions concerning suitable Finnish presidential candidates. Risto Ryti was the sole candidate not objected to by any of the three powers and was elected on 19 December.

In January 1941, Moscow demanded Finland relinquish control of the Petsamo mining area to the Soviets, but Finland, emboldened by a rebuilt defence force and German support, rejected the proposition. On 18 December 1940, Hitler officially approved Operation Barbarossa, paving the way for the German invasion of the Soviet Union, in which he expected both Finland and Romania to participate. Meanwhile, Finnish Major General

Paavo Talvela

Paavo Juho Talvela (born Paavo Juho Thorén 19 February 1897, died 30 September 1973) was a Finnish general of the infantry, Knight of the Mannerheim Cross and a member of the Jäger movement. He participated in the Eastern Front of World War ...

met with German

Franz Halder and

Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1 ...

in Berlin, the first time that the Germans had advised the Finnish government, in-carefully couched diplomatic terms, that they were preparing for war with the Soviet Union. Outlines of the actual plan were revealed in January 1941 and regular contact between Finnish and German military leaders began in February.

In the late spring of 1941, the USSR made a number of goodwill gestures to prevent Finland from completely falling under German influence. Ambassador

Ivan Zotov

Ivan () is a Slavic languages, Slavic male given name, connected with the variant of the Greek name (English: John (given name), John) from Hebrew language, Hebrew meaning 'God is gracious'. It is associated worldwide with Slavic countries. T ...

was replaced with the more flexible

Pavel Orlov

Pavel Maratovich Orlov (russian: Павел Маратович Орлов; born 8 December 1992) is a Russian former professional football player.

Club career

He made his Russian Football National League debut for FC Tambov on 27 July 2016 in ...

. Furthermore, the Soviet government announced that it no longer opposed a rapprochement between Finland and Sweden. Those conciliatory measures, however, did not have any effect on Finnish policy. Finland wished to re-enter the war mainly because of the Soviet invasion of Finland during the Winter War, which had taken place after Finnish intentions of relying on the League of Nations and Nordic neutrality to avoid conflicts had failed because of lack of outside support. Finland primarily aimed to reverse its territorial losses from the March 1940 Moscow Peace Treaty and, depending on the success of the German invasion of the Soviet Union, to possibly expand its borders, especially into

East Karelia. Some right-wing groups, such as the

Academic Karelia Society, supported a

Greater Finland

Greater Finland ( fi, Suur-Suomi; et, Suur-Soome; sv, Storfinland), an irredentist and nationalist idea, emphasized territorial expansion of Finland. The most common concept of Greater Finland saw the country as defined by natural borders enc ...

ideology.

German and Finnish war plans

The matter of when and why Finland prepared for war is still somewhat opaque. Historian

William R. Trotter stated that "it has so far proven impossible to pinpoint the exact date on which Finland was taken into confidence about Operation Barbarossa" and that "neither the Finns nor the Germans were entirely candid with one another as to their national aims and methods. In any case, the step from contingency planning to actual operations, when it came, was little more than a formality".

The inner circle of Finnish leadership, led by Ryti and Mannerheim, actively planned joint operations with Germany under a veil of ambiguous neutrality and without formal agreements after an alliance with Sweden had proved fruitless, according to a meta-analysis by Finnish historian

Olli Vehviläinen

Olli is a Dutch children's book character and a stuffed toy. The character Olli was created in 2004 by Dutch designer and film director Hein Mevissen and writer Diederiekje Bok as a character for a bottled mineral water. Olli was one of the many ...

. He likewise refuted the so-called "driftwood theory" that Finland had been merely a piece of driftwood that was swept uncontrollably in the rapids of great power politics. Even then, most historians conclude that Finland had no realistic alternative to co-operating with Germany. On 20 May, the Germans invited a number of Finnish officers to discuss the coordination of Operation Barbarossa. The participants met on 25–28 May in

Salzburg

Salzburg (, ; literally "Salt-Castle"; bar, Soizbuag, label= Austro-Bavarian) is the fourth-largest city in Austria. In 2020, it had a population of 156,872.

The town is on the site of the Roman settlement of ''Iuvavum''. Salzburg was founded ...

and Berlin and continued their meeting in Helsinki from 3 to 6 June. They agreed upon the arrival of German troops, Finnish mobilization and a general division of operations. They also agreed that the Finnish Army would start

mobilization

Mobilization is the act of assembling and readying military troops and supplies for war. The word ''mobilization'' was first used in a military context in the 1850s to describe the preparation of the Prussian Army. Mobilization theories and ...

on 15 June, but the Germans did not reveal the actual date of the assault. The Finnish decisions were made by the inner circle of political and military leaders, without the knowledge of the rest of the government, which were not informed until 9 June that mobilisation of

reservist

A reservist is a person who is a member of a military reserve force. They are otherwise civilians, and in peacetime have careers outside the military. Reservists usually go for training on an annual basis to refresh their skills. This person is ...

s, because of tensions between Germany and the Soviet Union, would be required.

Finland's relationship with Germany

Finland never signed the

Tripartite Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also known as the Berlin Pact, was an agreement between Germany, Italy, and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940 by, respectively, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Galeazzo Ciano and Saburō Kurusu. It was a defensive milit ...

, though it did sign the

Anti-Comintern Pact

The Anti-Comintern Pact, officially the Agreement against the Communist International was an anti-Communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on 25 November 1936 and was directed against the Communist International (C ...

, a less formal alliance, which the German leadership saw as a "litmus test of loyalty".

The Finnish leadership stated they would fight against the Soviets only to the extent needed to redress the balance of the 1940 treaty, though some historians consider that it had wider territorial goals under the slogan "shorter borders, longer peace". During the war, the Finnish leadership generally referred to the Germans as "brothers-in-arms" but also denied that they were allies of Germany – instead claiming to be "co-belligerents". For Hitler, the distinction was irrelevant since he saw Finland as an ally. The 1947 Paris Peace Treaty signed by Finland described Finland as having been "an ally of Hitlerite Germany" during the Continuation War.

In a 2008 poll of 28 Finnish historians carried out by ''

Helsingin Sanomat'', 16 said that Finland had been an ally of Nazi Germany, six said it had not been and six did not take a position.

Order of battle and operational planning

Soviet

The

Northern Front (russian: Северный фронт, links=no) of the

Leningrad Military District

The Leningrad Military District was a military district of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation. In 2010 it was merged with the Moscow Military District, the Northern Fleet and the Baltic Fleet to form the new Western Military District ...

was commanded by Lieutenant General

Markian Popov

Markian Mikhaylovich Popov (; 1902–1969) was a Soviet military commander, Army General (26 August 1943), and Hero of the Soviet Union (1965).

Early life

Markian Popov was born in 1902 in Ust-Medvediskaya in the Don Host Oblast (now Volgograd ...

and numbered around 450,000 soldiers in 18 divisions and 40 independent battalions in the Finnish region.

During the Interim Peace, the Soviet Military had relaid operational plans to conquer Finland, but with the German attack, Operation Barbarossa, begun on 22 June 1941, the Soviets required its best units and latest materiel to be deployed against the Germans and so abandoned plans for a renewed offensive against Finland. The

23rd Army was deployed in the Karelian Isthmus, the

7th Army to Ladoga Karelia and the

14th Army Fourteenth Army or 14th Army may refer to:

* 14th Army (German Empire), a World War I field Army

* 14th Army (Wehrmacht), a World War II field army

* Italian Fourteenth Army

* Japanese Fourteenth Army, a World War II field army, in 1944 converted ...

to the

Murmansk

Murmansk (Russian: ''Мурманск'' lit. "Norwegian coast"; Finnish: ''Murmansk'', sometimes ''Muurmanski'', previously ''Muurmanni''; Norwegian: ''Norskekysten;'' Northern Sámi: ''Murmánska;'' Kildin Sámi: ''Мурман ланнҍ'') ...

–

Salla

Salla (''Kuolajärvi'' until 1936) ( smn, Kyelijävri) is a municipality of Finland, located in Lapland. The municipality has a population of

() and covers an area of of

which

is water. The population density is

.

The nearby settlement of ...

area of Lapland. The Northern Front also commanded eight

aviation divisions. As the initial German strike against the

Soviet Air Forces

The Soviet Air Forces ( rus, Военно-воздушные силы, r=Voyenno-vozdushnyye sily, VVS; literally "Military Air Forces") were one of the air forces of the Soviet Union. The other was the Soviet Air Defence Forces. The Air Forces ...

had not affected air units located near Finland, it could deploy around 700 aircraft supported by a number of

Soviet Navy wings. The

Red Banner Baltic Fleet comprised 2 battleships, 2 light cruisers, 47 destroyers or large torpedo boats, 75 submarines, over 200 smaller craft as well as hundreds of aircraft—and outnumbered the ''

Kriegsmarine''.

Finnish and German

The Finnish Army () mobilised between 475,000 and 500,000 soldiers in 14 divisions and 3 brigades for the invasion, commanded by Field Marshal () Mannerheim. The army was organised as follows:

* II Corps (, ) and IV Corps: deployed to the Karelian Isthmus and comprised seven infantry divisions and one brigade.

*

Army of Karelia

The Army of Karelia ( fi, Karjalan armeija) was a Finnish army during the Continuation War.

The Army of Karelia was formed on 29 June 1941 soon after the start of the Continuation War.

Organisation

The army was organised in two corps and one se ...

: deployed north of Lake Ladoga and commanded by General

Erik Heinrichs

Axel Erik Heinrichs (21 July 1890 – 16 November 1965) was a Finnish military general. He was Finland's Chief of the General Staff during the Interim Peace and Continuation War (1940–1941 and 1942–1944) and commander-in-chief for a short t ...

. It comprised VI Corps, VII Corps and Group Oinonen; a total of seven divisions, including the German 163rd Infantry Division, and three brigades.

* 14th Division: deployed in the

Kainuu region, commanded directly by

Finnish Headquarters ().

Although initially deployed for a static defence, the Finnish Army was to later launch an attack to the south, on both sides of Lake Ladoga, putting pressure on Leningrad and thus supporting the advance of the German

Army Group North

Army Group North (german: Heeresgruppe Nord) was a German strategic formation, commanding a grouping of field armies during World War II. The German Army Group was subordinated to the ''Oberkommando des Heeres'' (OKH), the German army high comman ...

. Finnish intelligence had overestimated the strength of the Red Army, when in fact it was numerically inferior to Finnish forces at various points along the border. The army, especially its artillery, was stronger than it had been during the Winter War but included only one armoured battalion and had a general lack of motorised transportation. The

Finnish Air Force

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, equipment = 159

, equipment_label ...

() had 235 aircraft in July 1941 and 384 by September 1944, despite losses. Even with the increase in aircraft, the air force was constantly outnumbered by the Soviets.

The

Army of Norway

The Norwegian Army ( no, Hæren) is the land warfare service branch of the Norwegian Armed Forces. The Army is the oldest of the Norwegian service branches, established as a modern military organization under the command of the King of Norway ...

, or , comprising four divisions totaling 67,000 German soldiers, held the arctic front, which stretched approximately through Finnish Lapland. This army would also be tasked with striking Murmansk and the

Kirov (Murmansk) Railway during

Operation Silver Fox

Operation Silver Fox (german: Silberfuchs; fi, Hopeakettu) from 29 June to 17 November 1941, was a joint German– Finnish military operation during the Continuation War on the Eastern Front of World War II against the Soviet Union. The objecti ...

. The Army of Norway was under the direct command of the ''

Oberkommando des Heeres

The (; abbreviated OKH) was the high command of the Army of Nazi Germany. It was founded in 1935 as part of Adolf Hitler's rearmament of Germany. OKH was ''de facto'' the most important unit within the German war planning until the defeat at ...

'' () and was organised into

Mountain Corps Norway

Mountain Corps Norway (german: Gebirgskorps Norwegen) was a German army unit during World War II. It saw action in Norway and Finland.

The corps was formed in July 1940 and was later transferred to Northern Norway as part of '' Armeeoberkommand ...

and

XXXVI Mountain Corps with the Finnish

Finnish III Corps and 14th Division attached to it. The ''

Oberkommando der Luftwaffe

The (; abbreviated OKL) was the high command of the air force () of Nazi Germany.

History

The was organized in a large and diverse structure led by Reich minister and supreme commander of the Air force (german: Oberbefehlshaber der Luftwaf ...

'' () assigned 60 aircraft from ''

Luftflotte 5

Luftflotte 5 (Air Fleet 5) was one of the primary divisions of the German Luftwaffe in World War II. It was formed 12 April 1940 in Hamburg for the invasion of Norway.

It transferred to Oslo, Norway on 24 April 1940 and was the organization respo ...

'' (Air Fleet 5) to provide air support to the Army of Norway and the Finnish Army, in addition to its main responsibility of defending Norwegian air space. In contrast to the front in Finland, a total of 149 divisions and 3,050,000 soldiers were deployed for the rest of Operation Barbarossa.

Finnish offensive phase in 1941

Initial operations

In the evening of 21 June 1941, German mine-layers hiding in the

Archipelago Sea deployed two large minefields across the Gulf of Finland. Later that night, German bombers flew along the gulf to Leningrad, mining the harbour and the river

Neva

The Neva (russian: Нева́, ) is a river in northwestern Russia flowing from Lake Ladoga through the western part of Leningrad Oblast (historical region of Ingria) to the Neva Bay of the Gulf of Finland. Despite its modest length of , it ...

, making a refueling stop at

Utti Utti is a village in Valkeala, since 2009 a part of Kouvola, Finland. In 1918 General Carl Gustaf Mannerheim set up the first Finnish Air Force base in the village. Today, Utti is best known for the Utti Jaeger Regiment, a helicopter base and a t ...

, Finland, on the return leg. In the early hours of 22 June, Finnish forces launched

Operation Kilpapurjehdus

Operation Kilpapurjehdus ("Regatta") was the covername for the militarization of the Åland islands. The operation took place on June 22, 1941, and in this way, Finland strived to prevent Soviet landings in the area.

The Åland islands had been de ...

("Regatta"), deploying troops in the demilitarised

Åland

Åland ( fi, Ahvenanmaa: ; ; ) is an autonomous and demilitarised region of Finland since 1920 by a decision of the League of Nations. It is the smallest region of Finland by area and population, with a size of 1,580 km2, and a populat ...

. Although the 1921

Åland convention

The Åland convention, refers to two conventions regarding the demilitarization and neutralization of Åland.

* The Åland convention of 1856 was signed on 30 March 1856, following the Russian defeat in the Crimean War against the United Kingdom a ...

had clauses allowing Finland to defend the islands in the event of an attack, the coordination of this operation with the German invasion and the arrest of the Soviet consulate staff stationed on the islands, meant that the deployment was a deliberate violation of the treaty, according to Finnish historian

Mauno Jokipii

Mauno Jokipii (21 August 1924 – 2 January 2007) was a Finnish professor at the University of Jyväskylä in history specializing in World War II. He was a thorough investigator and a prolific author. Among his works were studies of the local hist ...

.

On the morning of 22 June Hitler's proclamation read: "Together with their Finnish comrades in arms the heroes from Narvik stand at the edge of the Arctic Ocean. German troops under command of the conqueror of Norway, and the Finnish freedom fighters under their Marshal's command, are protecting Finnish territory."

Following the launch of

Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

at around 3:15 a.m. on 22 June 1941, the Soviet Union sent seven bombers on a retaliatory airstrike into Finland, hitting targets at 6:06 a.m. Helsinki time as reported by the

Finnish coastal defence ship ''Väinämöinen''. On the morning of 25 June, the Soviet Union launched another air offensive, with 460 fighters and bombers targeting 19 airfields in Finland, however inaccurate intelligence and poor bombing accuracy resulted in several raids hitting Finnish cities, or municipalities, causing considerable damage. 23 Soviet bombers were lost in this strike while the Finnish forces lost no aircraft. Although the USSR claimed that the airstrikes were directed against German targets, particularly airfields, in Finland,

the

Finnish government

sv, Finlands statsråd

, border =

, image = File:Finnish Government logo.png

, image_size = 250

, caption =

, date =

, state = Republic of Finland

, polity =

, cou ...

used the attacks as justification for the approval of a "defensive war". According to historian David Kirby, the message was intended more for public opinion in Finland than abroad, where the country was viewed as an ally of the Axis powers.

Finnish advance in Karelia

The Finnish plans for the offensive in Ladoga Karelia were finalised on 28 June 1941, and the first stages of the operation began on 10 July.

By 16 July,

VI Corps 6 Corps, 6th Corps, Sixth Corps, or VI Corps may refer to:

France

* VI Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry formation of the Imperial French army during the Napoleonic Wars

* VI Corps (Grande Armée), a formation of the Imperial French army du ...

had reached the northern shore of

Lake Ladoga, dividing the Soviet 7th Army, which had been tasked with defending the area. The USSR struggled to contain the German assault, and soon the Soviet high command, ''

Stavka'', pulled all available units stationed along the Finnish border into the beleaguered front line. Additional reinforcements were drawn from the

237th Rifle Division

The 237th Rifle Division was an infantry division of the Red Army, originally formed in the months just before the start of the German invasion, based on the ''shtat'' (table of organization and equipment

A table of organization and equipment (TO ...

and the Soviet

10th Mechanised Corps, excluding the

198th Motorised Division, both of which were stationed in Ladoga Karelia, but this stripped much of the reserve strength of the Soviet units defending that area.

The Finnish

II Corps started its offensive in the north of the Karelian Isthmus on 31 July. Other Finnish forces reached the shores of Lake Ladoga on 9 August, encircling most of the three defending Soviet divisions on the northwestern coast of the lake in a

pocket (''

motti'' in Finnish); these divisions were later evacuated across the lake. On 22 August, the Finnish

IV Corps began its offensive south of II Corps and advanced towards

Vyborg

Vyborg (; rus, Вы́борг, links=1, r=Výborg, p=ˈvɨbərk; fi, Viipuri ; sv, Viborg ; german: Wiborg ) is a town in, and the administrative center of, Vyborgsky District in Leningrad Oblast, Russia. It lies on the Karelian Isthmus n ...

(). By 23 August, II Corps had reached the

Vuoksi River

The Vuoksi (russian: Вуокса, historically: "Uzerva"; fi, Vuoksi; sv, Vuoksen) is a river running through the northernmost part of the Karelian Isthmus from Lake Saimaa in southeastern Finland to Lake Ladoga in northwestern Russia. The ...

to the east and encircled the Soviet forces defending Vyborg.

The Soviet order to withdraw came too late, resulting in significant losses in materiel, although most of the troops were later evacuated via the

Koivisto Islands

Beryozovye Islands (russian: Берёзовые острова, Finnish: Koivisto, Swedish: Björkö; literally: "Birch Islands"), alternatively spelled Berezovye Islands, is an island group in Leningrad Oblast, Russia. The islands are situated at ...

. After suffering severe losses, the Soviet 23rd Army was unable to halt the offensive, and by 2 September the Finnish Army had reached the old

1939 border. The advance by Finnish and German forces split the Soviet Northern Front into the

Leningrad Front and the

Karelian Front

The Karelian Front russian: Карельский фронт) was a front (a formation of Army Group size) of the Soviet Union's Red Army during World War II, and operated in Karelia.

Wartime

The Karelian Front was created in August 1941 when ...

. On 31 August, Finnish Headquarters ordered II and IV Corps, which had advanced the furthest, to halt their advance along a line that ran from the Gulf of Finland via

Beloostrov

Beloostrov (russian: Белоо́стров; fi, Valkeasaari; ), from 1922 to World War II Krasnoostrov (russian: Красноо́стров, lit=Red Island, link=no), is a municipal settlement in Kurortny District of the federal city of St ...

–

Sestra River– Okhta River–

Lembolovo

Lembolovo (russian: Лемболово; fi, Lempaala) is a rural locality

In general, a rural area or a countryside is a geographic area that is located outside towns and cities. Typical rural areas have a low population density and sm ...

to Ladoga. The line ran past the former 1939 border, and approximately from Leningrad. There, they were ordered to take up a defensive position. On 1 September, the IV Corps engaged and defeated the Soviet 23rd Army near the town of

Porlampi

Sveklovichnoye (russian: Свеклови́чное) is a rural locality (a settlement) in Vyborgsky District of Leningrad Oblast, Russia, located on the Karelian Isthmus.

It was the site of the Battle of Porlampi, an engagement fought between ...

. Sporadic fighting continued around Beloostrov until the Soviets evicted the Finns on 20 September. The front on the Isthmus stabilised and the

siege of Leningrad began.

The Finnish Army of Karelia started its attack in East Karelia towards

Petrozavodsk

Petrozavodsk (russian: Петрозаводск, p=pʲɪtrəzɐˈvotsk; Karelian, Vepsian and fi, Petroskoi) is the capital city of the Republic of Karelia, Russia, which stretches along the western shore of Lake Onega for some . The population ...

,

Lake Onega

Lake Onega (; also known as Onego, rus, Оне́жское о́зеро, r=Onezhskoe ozero, p=ɐˈnʲɛʂskəɪ ˈozʲɪrə; fi, Ääninen, Äänisjärvi; vep, Änine, Änižjärv) is a lake in northwestern Russia, on the territory of the Repu ...

and the

Svir River

The Svir (, Veps: , Karelian/ Finnish: ) is a river in Podporozhsky, Lodeynopolsky, and Volkhovsky districts in the north-east of Leningrad Oblast, Russia. It flows westwards from Lake Onega to Lake Ladoga, thus connecting the two larges ...

on 9 September. German Army Group North advanced from the south of Leningrad towards the Svir River and captured

Tikhvin

Tikhvin (russian: Ти́хвин; Veps: ) is a town and the administrative center of Tikhvinsky District in Leningrad Oblast, Russia, located on both banks of the Tikhvinka River in the east of the oblast, east of St. Petersburg. Tikhvin ...

but were forced to retreat to the

Volkhov River

The Volkhov (russian: Во́лхов) is a river in Novgorodsky and Chudovsky Districts of Novgorod Oblast and Kirishsky and Volkhovsky Districts of Leningrad Oblast in northwestern Russia. It connects Lake Ilmen and Lake Ladoga and forms pa ...

by Soviet counterattacks. Soviet forces repeatedly attempted to expel the Finns from their

bridgehead

In military strategy, a bridgehead (or bridge-head) is the strategically important area of ground around the end of a bridge or other place of possible crossing over a body of water which at time of conflict is sought to be defended or taken over ...

south of the Svir during October and December but were repulsed; Soviet units attacked the German

163rd Infantry Division in October 1941, which was operating under Finnish command across the Svir, but failed to dislodge it. Despite these failed attacks, the Finnish attack in East Karelia had been blunted and their advance had halted by 6 December. During the five-month campaign, the Finns suffered 75,000 casualties, of whom 26,355 had died, while the Soviets had 230,000 casualties, of whom 50,000 became prisoners of war.

Operation Silver Fox in Lapland and Lend-Lease to Murmansk

The German objective in Finnish Lapland was to take Murmansk and cut the Kirov (Murmansk) Railway running from Murmansk to Leningrad by capturing Salla and

Kandalaksha

Kandalaksha (russian: Кандала́кша; fi, Kantalahti, also ''Kandalax'' or ''Candalax'' in the old maps; krl, Kannanlakši; sms, Käddluhtt) is a town in Kandalakshsky District of Murmansk Oblast, Russia, located at the head of Kandala ...

. Murmansk was the only year-round

ice-free port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Ha ...

in the north and a threat to the

nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow ...

mine at Petsamo. The joint Finnish–German Operation Silver Fox (german: Unternehmen Silberfuchs; fi, operaatio Hopeakettu, links=no) was started on 29 June 1941 by the German Army of Norway, which had the

Finnish 3rd and

6th Divisions under its command, against the defending Soviet 14th Army and

54th Rifle Division The 54th Rifle Division was an infantry division of the Soviet Union's Red Army and Soviet Army, formed twice. The division was formed in 1936 and fought in the Winter War. The division spent most of World War II in Karelia fighting with Finnish tr ...

. By November, the operation had stalled from the Kirov Railway due to unacclimatised German troops, heavy Soviet resistance, poor terrain, arctic weather and diplomatic pressure by the United States on the Finns regarding the lend-lease deliveries to Murmansk. The offensive and its three sub-operations failed to achieve their objectives. Both sides dug in and the arctic theatre remained stable, excluding minor skirmishes, until the Soviet

Petsamo–Kirkenes Offensive

The Petsamo–Kirkenes offensive was a major military offensive during World War II, mounted by the Red Army against the ''Wehrmacht'' in 1944 in the Petsamo region, ceded to the Soviet Union by Finland in accordance with the Moscow Armist ...

in October 1944.

The crucial

arctic lend-lease convoys from the US and the UK via Murmansk and Kirov Railway to the bulk of the Soviet forces continued throughout World War II. The US supplied almost

$11 billion in materials: 400,000 jeeps and trucks; 12,000 armored vehicles (including 7,000 tanks, which could equip some 20 US armoured divisions); 11,400 aircraft; and of food. As a similar example, British shipments of Matilda, Valentine and Tetrarch tanks accounted for only 6 percent of total Soviet tank production, but over 25 percent of medium and heavy tanks produced for the Red Army.

Aspirations, war effort and international relations

The ''Wehrmacht'' rapidly advanced deep into Soviet territory early in the Operation Barbarossa campaign, leading the Finnish government to believe that Germany would defeat the Soviet Union quickly. President Ryti envisioned a Greater Finland, where Finland and other

Finnic people

The Finnic or Fennic peoples, sometimes simply called Finns, are the nations who speak languages traditionally classified in the Finnic (now commonly '' Finno-Permic'') language family, and which are thought to have originated in the region of ...

would live inside a "natural defence borderline" by incorporating the

Kola Peninsula

sjd, Куэлнэгк нёа̄ррк

, image_name= Kola peninsula.png

, image_caption= Kola Peninsula as a part of Murmansk Oblast

, image_size= 300px

, image_alt=

, map_image= Murmansk in Russia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Murmansk Oblas ...

, East Karelia and perhaps even northern

Ingria

Ingria is a historical region in what is now northwestern European Russia. It lies along the southeastern shore of the Gulf of Finland, bordered by Lake Ladoga on the Karelian Isthmus in the north and by the River Narva on the border with Esto ...

. In public, the proposed frontier was introduced with the slogan "short border, long peace". Some members of the Finnish Parliament, such as members of the

Social Democratic Party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

Fo ...

and the

Swedish People's Party

The Swedish People's Party of Finland ( sv, Svenska folkpartiet i Finland (SFP); fi, Suomen ruotsalainen kansanpuolue (RKP)) is a political party in Finland aiming to represent the interests of the minority Swedish-speaking population of Finlan ...

, opposed the idea, arguing that maintaining the 1939 frontier would be enough. Finnish Commander-in-Chief, Field Marshal C. G. E. Mannerheim, often called the war an anti-Communist crusade, hoping to defeat "Bolshevism once and for all". On 10 July, Mannerheim drafted his order of the day, the

Sword Scabbard Declaration, in which he pledged to liberate Karelia; in December 1941 in private letters, he made known his doubts of the need to push beyond the previous borders. The Finnish government assured the United States that it was unaware of the order.

According to Vehviläinen, most Finns thought that the scope of the new offensive was only to regain what had been taken in the Winter War. He further stated that the term 'Continuation War' was created at the start of the conflict by the Finnish government to justify the invasion to the population as a continuation of the defensive Winter War. The government also wished to emphasise that it was not an official ally of Germany, but a 'co-belligerent' fighting against a common enemy and with purely Finnish aims. Vehviläinen wrote that the authenticity of the government's claim changed when the Finnish Army crossed the old frontier of 1939 and began to annex Soviet territory. British author

Jonathan Clements

Jonathan Michael Clements (born 9 July 1971) is a British author and scriptwriter. His non-fiction works include biographies of Confucius, Koxinga and Qin Shi Huang, as well as monthly opinion columns for ''Neo'' magazine. He is also the co-auth ...

asserted that by December 1941, Finnish soldiers had started questioning whether they were fighting a war of national defence or foreign conquest.

By the autumn of 1941, the Finnish military leadership started to doubt Germany's capability to finish the war quickly. The Finnish Defence Forces suffered relatively severe losses during their advance, and, overall, German victory became uncertain as German troops were

halted near Moscow. German troops in northern Finland faced circumstances they were unprepared for and failed to reach their targets. As the front lines stabilised, Finland attempted to start peace negotiations with the USSR. Mannerheim refused to assault Leningrad, which would inextricably tie Finland to Germany; he regarded his objectives for the war to be achieved, a decision that angered the Germans.

Due to the war effort, the Finnish economy suffered from a lack of labour, as well as food shortages and increased prices. To combat this, the Finnish government demobilised part of the army to prevent industrial and agricultural production from collapsing. In October, Finland informed Germany that it would need of grain to manage until next year's harvest. The German authorities would have rejected the request, but Hitler himself agreed. Annual grain deliveries of equaled almost half of the Finnish domestic crop. In November, Finland joined the

Anti-Comintern Pact

The Anti-Comintern Pact, officially the Agreement against the Communist International was an anti-Communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on 25 November 1936 and was directed against the Communist International (C ...

.

Finland maintained good relations with a number of other Western powers. Foreign volunteers from Sweden and Estonia were among the foreigners who joined Finnish ranks.

Infantry Regiment 200, called ("Finnish boys"), mostly comprised Estonians, and the Swedes mustered the

Swedish Volunteer Battalion. The Finnish government stressed that Finland was fighting as a

co-belligerent

Co-belligerence is the waging of a war in cooperation against a common enemy with or without a formal treaty of military alliance. Generally, the term is used for cases where no alliance exists. Likewise, allies may not become co-belligerents in a ...

with Germany against the USSR only to protect itself and that it was still the same democratic country as it had been in the Winter War. For example, Finland maintained diplomatic relations with the exiled Norwegian government and more than once criticised German occupation policy in Norway. Relations between Finland and the United States were more complex since the American public was sympathetic to the "brave little democracy" and had anticommunist sentiments. At first, the United States sympathised with the Finnish cause, but the situation became problematic after the Finnish Army had crossed the 1939 border. Finnish and German troops were a threat to the Kirov Railway and the northern supply line between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union. On 25 October 1941, the US demanded that Finland cease all hostilities against the USSR and to withdraw behind the 1939 border. In public, President Ryti rejected the demands, but in private, he wrote to Mannerheim on 5 November and asked him to halt the offensive. Mannerheim agreed and secretly instructed General

Hjalmar Siilasvuo

Hjalmar Fridolf Siilasvuo (born Hjalmar Fridolf Strömberg, 18 March 1892 – 11 January 1947) was a Finnish lieutenant general ( fi, kenraaliluutnantti, link=no), a knight of the Mannerheim Cross and a member of the Jäger Movement. He particip ...

and his III Corps to end the assault on the Kirov Railway.

British declaration of war and action in the Arctic Ocean

On 12 July 1941, the United Kingdom signed an agreement of joint action with the Soviet Union. Under German pressure, Finland closed the British

legation in Helsinki and cut diplomatic relations with Britain on 1 August. The most sizable British action on Finnish soil was the

Raid on Kirkenes and Petsamo

Operation EF (1941), also the Raid on Kirkenes and Petsamo took place on 30 July 1941, during the Second World War. After the beginning of Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, Fleet Air Arm aircraft fle ...

, an aircraft-carrier strike on German and Finnish ships on 31 July 1941. The attack accomplished little except the loss of one Norwegian ship and three British aircraft, but it was intended to demonstrate British support for its Soviet ally.

From September to October in 1941, a total of 39

Hawker Hurricane

The Hawker Hurricane is a British single-seat fighter aircraft of the 1930s–40s which was designed and predominantly built by Hawker Aircraft Ltd. for service with the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was overshadowed in the public consciousness b ...

s of

No. 151 Wing RAF, based at Murmansk, reinforced and provided pilot-training to the Soviet Air Forces during

Operation Benedict

Operation Benedict (29 July – 6 December 1941) was the establishment of Force Benedict with units of the Soviet Air Forces (VVS, ) in north Russia, during the Second World War. The force comprised 151 Wing Royal Air Force (RAF), with two squadr ...

to protect arctic convoys.

On 28 November, the British government presented Finland with an ultimatum demanding for the Finns to cease military operations by 3 December. Unofficially, Finland informed the Allies that Finnish troops would halt their advance in the next few days. The reply did not satisfy London, which declared war on Finland on 6 December. The

Commonwealth nations of Canada, Australia,

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

and

New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

soon followed suit. In private, British Prime Minister

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

had sent a letter to Mannerheim on 29 November in which Churchill was "deeply grieved" that the British would have to declare war on Finland because of the British alliance with the Soviets. Mannerheim repatriated British volunteers under his command to the United Kingdom via Sweden. According to Clements, the declaration of war was mostly for appearance's sake.

Trench warfare from 1942 to 1944

Unconventional warfare and military operations

Unconventional warfare was fought in both the Finnish and Soviet wildernesses. Finnish

long-range reconnaissance patrol

A long-range reconnaissance patrol, or LRRP (pronounced "lurp"), is a small, well-armed reconnaissance team that patrols deep in enemy-held territory.Ankony, Robert C., ''Lurps: A Ranger's Diary of Tet, Khe Sanh, A Shau, and Quang Tri,'' revised ...

s, organised both by the

Intelligence Division's

Detached Battalion 4

Detached Battalion 4 ( ()) was a special forces unit of the Finnish Army during the Continuation War and Lapland War, serving from July 1943 to November 1944. The battalion was founded under the Intelligence Division of Defence Command from the ...

and by local units, patrolled behind Soviet lines.

Soviet partisans

Soviet partisans were members of resistance movements that fought a guerrilla war against Axis forces during World War II in the Soviet Union, the previously Soviet-occupied territories of interwar Poland in 1941–45 and eastern Finland. The ...

, both resistance fighters and regular long-range patrol detachments, conducted a number of operations in Finland and in

Eastern Karelia from 1941 to 1944. In summer 1942, the USSR formed the 1st Partisan Brigade. The unit was 'partisan' in name only, as it was essentially 600 men and women on long-range patrol intended to disrupt Finnish operations. The 1st Partisan Brigade was able to infiltrate beyond Finnish patrol lines, but was intercepted, and rendered ineffective, in August 1942 at

Lake Segozero

Lake Segozero (, ) is a large freshwater lake in the Republic of Karelia, northwestern part of Russia. It is located at . The Segezha is a major outflow from Segozero and it empties to Vygozero. After the hydroelectric power plant

Hydroel ...

.

Irregular partisans distributed propaganda newspapers, such as Finnish translations of the official

Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of ''The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. ...

paper ''

Pravda

''Pravda'' ( rus, Правда, p=ˈpravdə, a=Ru-правда.ogg, "Truth") is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most influential papers in the ...

'' (). Notable Soviet politician,

Yuri Andropov

Yuri Vladimirovich Andropov (– 9 February 1984) was the sixth paramount leader of the Soviet Union and the fourth General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. After Leonid Brezhnev's 18-year rule, Andropov served in the p ...

, took part in these partisan guerrilla actions. Finnish sources state that, although Soviet partisan activity in East Karelia disrupted Finnish military supply and communication assets, almost two thirds of the attacks targeted civilians, killing 200 and injuring 50, including children and elderly.

[.]

Between 1942 and 1943, military operations were limited, although the front did see some action. In January 1942, the Soviet Karelian Front attempted to retake

Medvezhyegorsk

Medvezhyegorsk (russian: Медвежьего́рск; krl, Karhumägi; fi, Karhumäki) is a town and the administrative center of Medvezhyegorsky District of the Republic of Karelia, Russia. Population: 15,800 (1959).

History

A village in ...

(), which had been lost to the Finns in late 1941. With the arrival of spring in April, Soviet forces went on the offensive on the Svir River front, in the

Kestenga

Kestenga (russian: Кестеньга; krl, Kiestinki; fi, Kiestinki), is a rural village in the Loukhsky District of the Republic of Karelia in Russia on the northern shore of Lake Topozero.

It is the administrative centre of the ''Kestenga r ...

() region further north in Lapland as well as in the far north at Petsamo with the

14th Rifle Division's amphibious landings supported by the

Northern Fleet

Severnyy flot

, image = Great emblem of the Northern Fleet.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Northern Fleet's great emblem

, start_date = June 1, 1733; Sov ...

. All Soviet offensives started promisingly, but due either to the Soviets overextending their lines or stubborn defensive resistance, the offensives were repulsed. After Finnish and German counterattacks in Kestenga, the front lines were generally stalemated. In September 1942, the USSR attacked again at Medvezhyegorsk, but despite five days of fighting, the Soviets only managed to push the Finnish lines back on a roughly -long stretch of the front. Later that month, a Soviet landing with two battalions in Petsamo was defeated by a German counterattack. In November 1941, Hitler decided to separate the German forces fighting in Lapland from the Army of Norway and create the Army of Lapland, commanded by

Eduard Dietl

Eduard Wohlrat Christian Dietl (21 July 1890 – 23 June 1944) was a German general during World War II who commanded the 20th Mountain Army. He was magnanimously awarded of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords of Na ...

through . In June 1942, the Army of Lapland was redesignated the

20th Mountain Army.

Siege of Leningrad and naval warfare

In the early stages of the war, the Finnish Army overran the former 1939 border, but ceased their advance from the center of Leningrad. Multiple authors have stated that Finland participated in the siege of Leningrad (), but the full extent and nature of their participation is debated and a clear consensus has yet to emerge. American historian

David Glantz

David M. Glantz (born January 11, 1942) is an American military historian known for his books on the Red Army during World War II and as the chief editor of '' The Journal of Slavic Military Studies''.

Born in Port Chester, New York, Glantz re ...

, writes that the Finnish Army generally maintained their lines and contributed little to the siege from 1941 to 1944, whereas Russian historian

Nikolai Baryshnikov stated in 2002 that Finland tacitly supported Hitler's starvation policy for the city. However, in 2009 British historian

Michael Jones disputed Baryshnikov's claim and asserted that the Finnish Army cut off the city's northern supply routes but did not take further military action.

In 2006, American author

Lisa A. Kirchenbaum wrote that the siege started "when German and Finnish troops severed all land routes in and out of Leningrad."

According to Clements, Mannerheim personally refused Hitler's request of assaulting Leningrad during

their meeting on 4 June 1942. Mannerheim explained to Hitler that "Finland had every reason to wish to stay out of any further provocation of the Soviet Union." In 2014, author

Jeff Rutherford described the city as being "ensnared" between the German and Finnish armies.

British historian

John Barber described it as a "siege by the German and Finnish armies from 8 September 1941 to 27 January 1944

.. in his foreword in 2017.

Likewise, in 2017,

Alexis Peri wrote that the city was "completely cut off, save a heavily patrolled water passage over Lake Ladoga" by "Hitler's Army Group North and his Finnish allies."

The 150 speedboats, two minelayers and four steamships of the

Finnish Ladoga Naval Detachment, as well as numerous shore batteries, had been stationed on Lake Ladoga since August 1941. Finnish Lieutenant General Paavo Talvela proposed on 17 May 1942 to create a joint Finnish–German–Italian unit on the lake to disrupt Soviet supply convoys to Leningrad. The unit was named

Naval Detachment K and comprised four Italian

MAS torpedo motorboats of the

XII Squadriglia MAS, four German KM-type minelayers and the Finnish

torpedo-motorboat ''Sisu''. The detachment began operations in August 1942 and sank numerous smaller Soviet watercraft and flatboats and assaulted enemy bases and beach fronts until it was dissolved in the winter of 1942–43.

Twenty-three

Siebel ferries and nine infantry transports of the German ''

Einsatzstab Fähre Ost'' were also deployed to Lake Ladoga and unsuccessfully

assaulted the island of Sukho, which protected the main supply route to Leningrad, in October 1942.

Despite the siege of the city, the Soviet Baltic Fleet was still able to operate from Leningrad. The Finnish Navy's flagship had been sunk in September 1941 in the gulf by mines during the failed diversionary

Operation Nordwind (1941)

Operation North Wind (german: Unternehmen Nordwind) was a joint German-Finnish naval operation in the Baltic Sea in 1941, in the course of World War II. The operation itself was a distracting manoeuvre so that another German force could occupy the ...

. In early 1942, Soviet forces recaptured the island of

Gogland

Gogland or Hogland (russian: Гогланд, transliteration from original sv, Hogland; fi, Suursaari) is an island in the Gulf of Finland in the eastern Baltic Sea, about 180 km west from Saint Petersburg and 35 km from the coas ...

, but lost it and the

Bolshoy Tyuters

Bolshoi Tyuters (russian: Большой Тютерс; fi, Tytärsaari; et, Suur Tütarsaar; sv, Tyterskär) is an island in the Gulf of Finland of the Baltic Sea, located away from the coast of Finland, to the south-east from Hogland. The is ...

islands to Finnish forces later in spring 1942. During the winter between 1941 and 1942, the Soviet Baltic Fleet decided to use their large submarine fleet in offensive operations. Though initial submarine operations in the summer of 1942 were successful, the and

Finnish Navy

The Finnish Navy ( fi, Merivoimat, sv, Marinen) is one of the branches of the Finnish Defence Forces. The navy employs 2,300 people and about 4,300 conscripts are trained each year. Finnish Navy vessels are given the ship prefix "FNS", short f ...

soon intensified their anti-submarine efforts, making Soviet submarine operations later in 1942 costly. The underwater offensive carried out by the Soviets convinced the Germans to lay

anti-submarine net

An anti-submarine net or anti-submarine boom is a boom placed across the mouth of a harbour or a strait for protection against submarines.

Examples of anti-submarine nets

* Lake Macquarie anti-submarine boom

* Indicator net

* Naval operations in ...

s as well as supporting minefields between Porkkala Peninsula and

Naissaar, which proved to be an insurmountable obstacle for Soviet submarines. On the

Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

,

Finnish radio intelligence intercepted Allied messages on supply convoys to Murmansk, such as

PQ 17

PQ 17 was the code name for an Allies of World War II, Allied Arctic convoys, Arctic convoy during the Second World War. On 27 June 1942, the ships sailed from Hvalfjörður, Iceland, for the port of Arkhangelsk in the Soviet Union. The convoy was ...

and

PQ 18, and relayed the information to the ''

Abwehr'', German intelligence.

Finnish military administration and concentration camps

On 19 July 1941, the Finns created a military administration in occupied East Karelia with the goal of preparing the region for eventual incorporation into Finland. The Finns aimed to

expel the Russian portion of the local population (constituting to about a half), who were deemed "non-national", from the area once the war was over, and replace them with the local

Finnic peoples

The Finnic or Fennic peoples, sometimes simply called Finns, are the nations who speak languages traditionally classified in the Finnic (now commonly '' Finno-Permic'') language family, and which are thought to have originated in the region of ...

, such as

Karelians

Karelians ( krl, karjalaižet, karjalazet, karjalaiset, Finnish: , sv, kareler, karelare, russian: Карелы) are a Finnic ethnic group who are indigenous to the historical region of Karelia, which is today split between Finland and Russi ...

,

Finns

Finns or Finnish people ( fi, suomalaiset, ) are a Baltic Finnic ethnic group native to Finland.

Finns are traditionally divided into smaller regional groups that span several countries adjacent to Finland, both those who are native to these ...

,

Ingrians

The Ingrians ( fi, inkeriläiset, ; russian: Ингерманландцы, translit=Ingermanlandts'i), sometimes called Ingrian Finns, are the Finnish people, Finnish population of Ingria (now the central part of Leningrad Oblast in Russia), des ...

and

Vepsians

Veps, or Vepsians ( Veps: ''vepsläižed''), are a Finnic people who speak the Veps language, which belongs to the Finnic branch of the Uralic languages.

According to the 2002 census, there were 8,240 Veps in Russia. Of the 281 Veps in Ukraine ...